‘œIt is not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.’ ‘”Edmund Hillary

Mountains produce the best adventure stories. Actually, that’ s not quite true. Climbers produce the best stories. Mountains don’

s not quite true. Climbers produce the best stories. Mountains don’ t give a damn.

t give a damn.

And that, of course, is part of the magic.

These vast, beautiful beasts that soar above us – secular cathedrals, perhaps – tempting us to raise our eyes upwards, wondering if it’ s possible, if it’

s possible, if it’ ll ‘˜go’

ll ‘˜go’ , wondering if we are up to the task. They do not care about our feeble futile efforts on their flanks. And yet the sacrifice, the suffering, the efforts, the guts, the risks that mountaineers pour forth in their desperate efforts to reach the top (and then back down to the bottom) is nothing short of the very limit of human potential and zealous fanaticism.

, wondering if we are up to the task. They do not care about our feeble futile efforts on their flanks. And yet the sacrifice, the suffering, the efforts, the guts, the risks that mountaineers pour forth in their desperate efforts to reach the top (and then back down to the bottom) is nothing short of the very limit of human potential and zealous fanaticism.

The rewards are preposterous: to stand on the highest bit and get a slightly nicer view than you do a little lower down seems a crazy thing to risk so much for. For the risks are always there with climbers. All top-level climbers have tales of when they nearly died doing what they love. They all have friends or colleagues who have died in the mountains. And some of them will die themselves in the same way. There is a dark side to the mountains. They know that. But still they do it.

A love deemed worth dying for is a powerful love indeed. It’ s a love affair based upon risk and ego and ambition. But it is one made possible and sustained by effort, and hope, and collaboration, and empathy, and patience, and persistence and and caring, and by serving an apprenticeship, and mastering your craft and the good bits of pride. It’

s a love affair based upon risk and ego and ambition. But it is one made possible and sustained by effort, and hope, and collaboration, and empathy, and patience, and persistence and and caring, and by serving an apprenticeship, and mastering your craft and the good bits of pride. It’ s totally bloody daft. It is, as Yvon Chouinard put it, pointless but meaningful. I prefer that explanation to the hackneyed ‘˜because it’

s totally bloody daft. It is, as Yvon Chouinard put it, pointless but meaningful. I prefer that explanation to the hackneyed ‘˜because it’ s there’

s there’ .

.

Pointless but meaningful: that might just be a perfect subtitle for my new book, for my life, and one which all the other tramps like us who are crazed by wanderlust will surely understand.

I am not a mountaineer, though I wish that I was. I’m m not a mountaineer because I have been reluctant to put in the time necessary to learn the skills to climb something exciting and stay alive. So I admire mountaineers for being something which that I am not. I like the way they can choose between solitude and camaraderie. I love the untouched simplicity of mountain tops, and how beautiful they look from down in the valley as well as up on the windy heights.

m not a mountaineer because I have been reluctant to put in the time necessary to learn the skills to climb something exciting and stay alive. So I admire mountaineers for being something which that I am not. I like the way they can choose between solitude and camaraderie. I love the untouched simplicity of mountain tops, and how beautiful they look from down in the valley as well as up on the windy heights.

From my own few mountain experiences, I have happy memories of rasping for breath with each small footstep, kicking crampons into the snow to create a small step for my partner below me, roped to me, below in the South American Andes. 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10. I counted the steps in my head as I struggled for breath. And after the tenth I treated myself to a little break. Gazing down from almost 6000 metres the world below looked so impossibly small and unreal. And then turn, kick, climb once more.

The high camp, with your tent teetering impossibly high, is a special place to be. So, too, is the thrill of rock climbing, though the fear of what climbers call ‘˜exposure’ (the bloody big drop beneath your feet) is enough to cripple any rock-climbing aspirations I may ever have had. I’m

(the bloody big drop beneath your feet) is enough to cripple any rock-climbing aspirations I may ever have had. I’m m intrigued by this fear and I enjoy challenging it. After all, if you are securely tied to a rope then you are very safe. But the mind struggles with the difference between perceived risk and actual danger.

m intrigued by this fear and I enjoy challenging it. After all, if you are securely tied to a rope then you are very safe. But the mind struggles with the difference between perceived risk and actual danger.

I like learning that lesson, though I am aware that I am unlikely ever to be brave enough to climb El Cap in Yosemite. Even Scotland’ s Innaccessible Pinnacle had me clinging tight to the rock with fear (though simultaneously whooping with delight). But whilst rock climbing to a serious level is probably out for me, I do harbour an ambition to climb a large mountain in Greenland or Central Asia. This is surprising to myself, for I don’

s Innaccessible Pinnacle had me clinging tight to the rock with fear (though simultaneously whooping with delight). But whilst rock climbing to a serious level is probably out for me, I do harbour an ambition to climb a large mountain in Greenland or Central Asia. This is surprising to myself, for I don’ t care about world records and so on. Yet still the prospect of a first ascent – a mountain never before climbed before – really captures my imagination.

t care about world records and so on. Yet still the prospect of a first ascent – a mountain never before climbed before – really captures my imagination.

Mountaineering and climbing require skill, commitment and time. But that is no reason not to begin. Every climber interviewed in my book once had to learn how to do everything: use a karabiner, first climb a small hill, trek up an easy mountain. You can too. You just have to begin.

Just bear in mind as you do it though the crazy, obsessive affair that you might just be opening the door to.

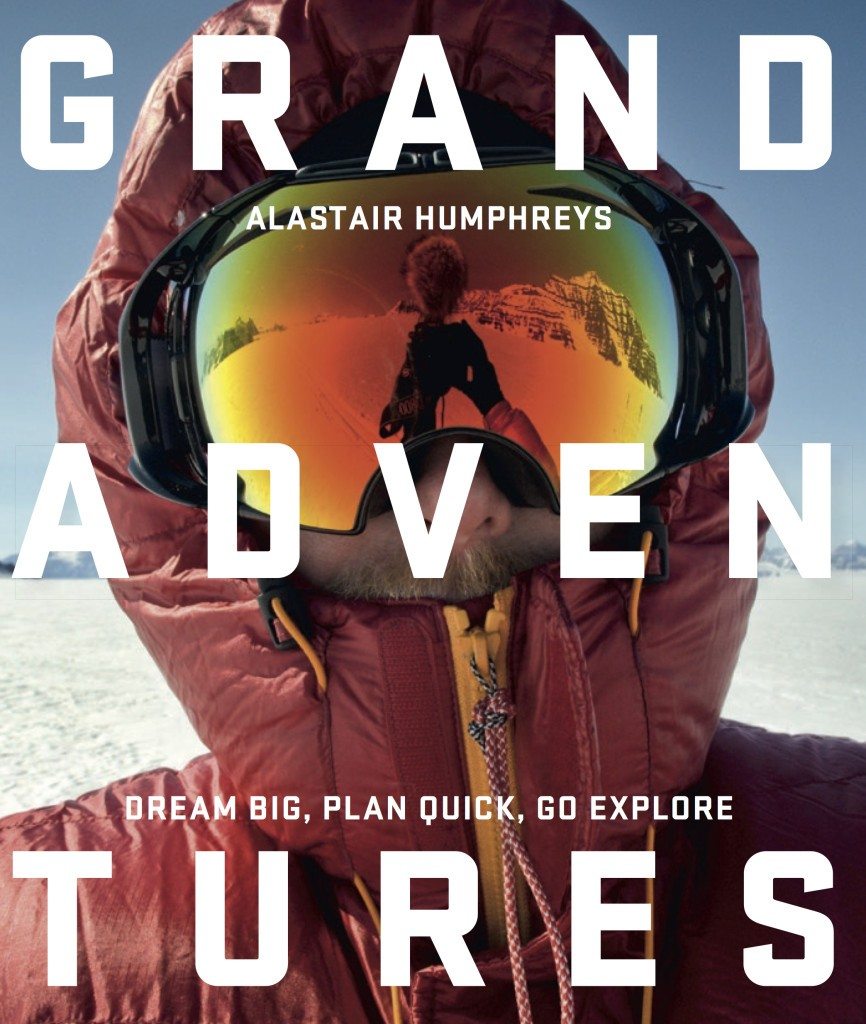

My new book, Grand Adventures, answers many questions such as this. It’s designed to help you dream big, plan quick, then go explore. There are also interviews and expertise from around 100 adventurers, plus masses of great photos to get you excited.

I would be extremely grateful if you bought a copy here today!

I would also be really thankful if you could share this link on social media with all your friends – http://amzn.to/20IMYDt. It honestly would help me far more than you realise.

Thank you so much!

Grand Adventures from Alastair Humphreys on Vimeo.

The post Why Everyone Should Climb a Mountain appeared first on Alastair Humphreys.